Connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans: a historic challenge

A gateway between North and South America, between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the Panama Canal remains one of the most challenging engineering projects ever undertaken. A major nerve centre, it crystallised political and economic issues that sometimes led to scandals and influenced the geopolitics of the region. It is still an unavoidable route for global shipping trade, cruises in Central America and trips to Panama.

Building a canal in Panama: a project long in the offing

Some would call it a slightly crazy dream, others, a daring gamble. The idea of cutting across the isthmus of Panama came about during the reign of Charles Quint, King of Spain, in the 16th century. This canal, a historical project and world wonder, can be crossed today when cruising in Panama.

More than three centuries later, the project caught the eye of French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps. Following the successful opening of the Suez canal in 1869, he chaired the international interoceanic canal congress in Paris in 1879. He convinced representatives of 26 nations, including the United States, to dig a new sea-level canal in Panama on a concession obtained from the Colombian government* by Lucien Bonaparte-Wyse, great-nephew of Napoleon I, one year earlier.

*Panama was a part of Colombia until it declared independence, backed by the United States, in 1903.

A shortcut saving more than 14,000 km connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans

With his project accepted, Ferdinand de Lesseps now had to raise 600 million francs to see his 74 kilometre long, 22 metre wide, and 9 metre deep canal form a path between the Atlantic and the Pacific.

Feeling self-confident, he promoted the canal in the press. Feeling self-confident, he claimed the canal would take eight years to build, promising that ships crossing the canal would save 14,000 kilometres, a great boon to the shipping industry. In the end, it took 32 years to build the waterway and the construction was tarnished by a scandal that left a lasting mark on France’s political and industrial class.

One problem after another

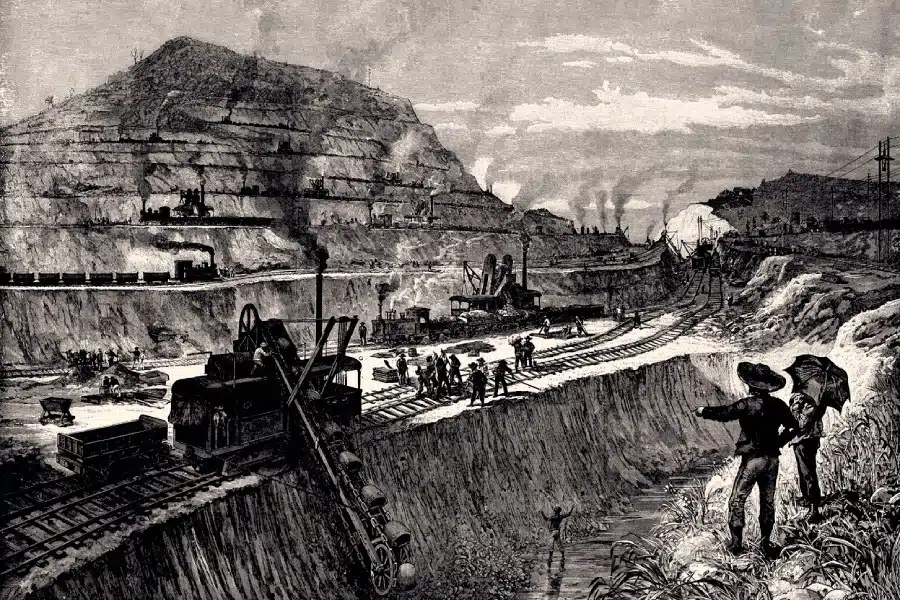

Preliminary works began in February 1881. Lesseps did not manage to raise the necessary funds, but remained optimistic. He firmly believed that he could recreate the Suez project. But the situation was different. He didn’t listen to the engineers involved in the project, including Gustave Eiffel. They advised him to build a lock canal, which would be cheaper than a sea-level canal, and more suited to the Panamanian landscapes.

In addition to landslides following torrential rain, the project was hit by epidemics of malaria and yellow fever. It is currently estimated that the project brought about the death of 25,000 workers.

Ruin and scandal on the Panama Canal

Delays continued to mount and, in 1884, the company had run out of money, while just one-tenth of planned excavations had gone ahead.

To ensure they could keep digging the canal, Ferdinand de Lesseps decided to issue lottery bonds in order to raise new funds from small investors. But to do this, he needed to change the law. And so he surrounded himself with industrialists close to members of parliament and press owners. The bonds were promoted in the newspapers they owned. Politicians were bribed to support a revised and corrected law. It was finally passed in 1888. One year earlier, Lesseps had also resolved to listen to Gustave Eiffel. He abandoned the sea-level canal for a lock canal. However, he was too late: the company went bankrupt in 1889, leading 85,000 investors to financial ruin.

An enquiry into breach of trust and fraud was launched at the government’s request in 1891, sullying the entire political class. Ferdinand de Lesseps and his son, Charles, were sentenced to five years in prison. Due to his advanced age and a procedural irregularity, the engineer did not serve his sentence.

Completion and inauguration of the canal: France passes the baton to the United States

Work did not resume until the start of the 20th century, with the company’s shares being sold to the Americans. Under threat of reprisals, Colombia handed over the canal project to the United States. The Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty was signed on 18th November 1903, giving the United States complete control of the canal.

Construction was completed between 1903 and 1913. The canal was opened on 15th August 1914, with little attention from France, which had just gone to war.

Photos credits : © Istock / © Studio PONANT / Léa Paulin

PONANT takes you there

Head to Central America to immerse yourself in the past and enjoy the lush countryside.