Of Dogs and Men

Alaskan Malamutes, Siberian Huskies, Greenland Dogs and Samoyeds: all these sled dogs are emblematic of the Far North, descended from wolves with whom they share their pack and survival instincts. These robust, powerful animals have incredible stamina and have accompanied mushers in the polar regions for thousands of years. The Inuit, gold prospectors, explorers and lovers of the great outdoors have all added their own chapter to the dog sledding story.

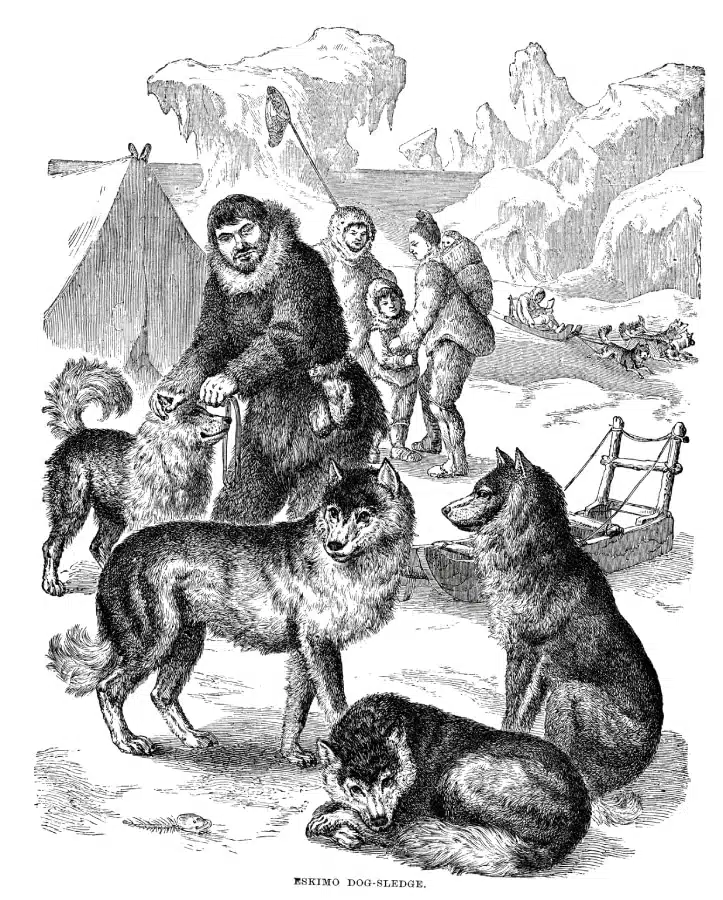

Dog sledding: an ancestral practice

Although the term “musher” is relatively new*, dog sledding is an ancestral practice with roots dating back roughly 5,000 to 6,000 years. “For the inhabitants of the Arctic, this was the only way to get around,” explains John Perrolaz, who has worked as a musher in the Queyras since 2008. The practice goes back to the domestication of wolves who, once tamed and harnessed to a sled, gave these indigenous peoples the opportunity to expand their hunting and fishing grounds. “These sleds enabled them to colonise the hostile areas of the Far North. Without dogs, they couldn’t have survived.” Dog sledding is an ancient practice, but in some of Greenland’s most remote regions, such as Qaanaaq in the North and Ittoqqortoormiit in the East, it is still part of the daily lives of the Inuit populations. These areas are surrounded by sea ice nine months of the year, so mushing is taught from an early age, and sled dogs are still hunting and fishing companions, essential for the survival of the inhabitants of these extreme environments.

Prospectors: working like a dog

In the late 19th century, the promised land for nearly 100,000 prospectors was called the Klondike, a region of the western Yukon territory in Canada. It was the famous Gold Rush era, and between 1896 and 1898, nearly 5,000 dogs arrived at Dawson City, the base camp. Why? To provide transport. Tens of thousands of migrants who came to seek their fortune and new adventures incorporated mushing into their way of life. Sled dogs were everywhere and increasingly became part of popular culture. In addition to gold and men, they tirelessly carried food, equipment, wood and mail. It was around this time, in August 1897, that a penniless young Jack London reached Dawson City. Although he did not return home a rich man, he later turned his experiences into literary gold, namely The Call of the Wild and White Fang.

Dogs in “pole” position

Reaching the Poles has always been a challenge for humanity, even more so than finding gold. Yet, without sled dogs, there would have been no polar exploration. They were involved in the excitement of the race to terra incognita from the very beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Five tireless Greenland Dogs accompanied Jean-Baptiste Charcot aboard Le Français on his first expedition to Antarctica (1903-1905). Dogs also pulled Paul-Émile Victor’s sled during his exploration of Adélie Land in 1956. Between these two expeditions were two other notable feats. In 1909, Robert Peary and Frederick Cook both claimed to have reached the North Pole first (this remains controversial to this day), and in 1911, Roald Amundsen was the first to reach the South Pole. All these explorers had sled dogs who proved to be valuable allies, whether for transporting equipment or guiding men. “During a whiteout in the middle of a storm, you can’t see anything,” explains John Perrolaz. “We have neither their sense of smell nor their ability to see and get our bearings in the snow. Without dogs, the men would have been lost.”

Winter soldiers

On the strength of their polar exploits, sled dogs were on the front lines in Norway and the Vosges mountains during the First World War. “400 Alaskan Malamutes served France, supplying the trenches and recovering the injured at the front,” says John Perrolaz. “Musher-soldiers were specially trained for these operations.” The ‘Alaskan Dog’ project, as it was known, was approved by the French government in 1915. In the end, 400 dogs were to be mobilised for 70 sleds… and 5 tonnes of biscuits. And at the end of the war, three of the dogs were awarded the Croix de Guerre medal for their heroism!

Mushing: the serum run

In addition to transportation, dog sleds are now also used for recreational purposes. Mushing was officially recognised as a sport in Nome, on the far western tip of Alaska, with the launch of the first competition in 1908. Nome was also where, in 1925, a diphtheria epidemic led to the creation of what remains today, along with the Yukon Quest in Canada, the most iconic dog sled race in the world: the Iditarod. During this serum run, a relay of 20 mushers travelled night and day to cross over 1,000 km to bring the precious antidote from the south in just six days! The serum arrived in Nome on 2 February 1925, carried by Gunnar Kaasen and his lead dog, a Siberian Husky who was destined to become a star, perhaps you know his name: Balto.

For the love of dogs

Although there were 30,000 sled dogs in Greenland ten years ago, there are only 12,000 today. But in all regions that are covered in snow during winter, passionate mushers who love the great outdoors strive to perpetuate this ancestral practice. It is much more than a job. It is a passion, which they share with visitors during guided walks and other nature activities. Rather than being hunters or explorers, mushers today tend to be specialists in their environment, sharing its secrets, fauna and flora. Take John Perrolaz, who owns some thirty dogs, as example: “Winter and summer we are [in the Alps] offering sledding, cani-hiking [walking attached to a dog] and cani-cross [cross country running attached to a dog]. In spring, I take them to Sweden to enjoy the great outdoors.” Driving a dog sled is something you have to do every day. And John Perrolaz knows everything about his dogs. But it’s much more than that; he has a deep connection with them, anticipating their expectations and moods: whether they are tired, excited or upset. “You have to truly love your dogs and make them part of your life,” says John Perrolaz, “and love the sharing aspect of dog sledding. This brings us back to the idea of the symbiosis that humans were originally able to create with wolves.” They offer a beautiful lesson in humility, a step in the quest for self-discovery: “Dogs remind us who we are.”

Did you know ?

The term “musher” derives from the French word “marche”, meaning “go” or “run”, which was anglicised in the late 18th century when the French ceded Canada to the English.

Photos Credit : © Studio PONANT / Nicolas Dubreuil / © istock photo / © Studio PONANT / Nath Michel

Explore the Far North

Discover the cultures and traditions of the Arctic peoples